Holland & Holland’s Mighty .700 Nitro Express

Holland & Holland’s .700 NE Royal de Luxe is a side-lock double with 26″ barrels and weighs 18 lbs. It features the finest deluxe-grade walnut and ornate engraving masterfully executed by the renowned Brown brothers of Swindon, U.K.

Despite owning a large number of best-quality double rifles, Beverly Hills businessman William Feldstein had never ordered a double gun to his own specifications. All the rifles he bought had been made for other people “back in the day.” As the crown to his impressive collection, he wanted to add a battery of big-bore rifles so, in 1985, he paid a visit to Holland & Holland’s prestigious shop in London … check in hand. He was there to order a set of four Nitro Express (NE) double rifles tailor-made to his personal preferences. He wanted the set to include large, elephant-capable chamberings: a .375 NE; a .500/.465 NE; a .577 NE; and a .600 NE.

- Activate Your Own Stem Cells & Reverse The Aging Process - Choose "Select & Save" OR Join, Brand Partner & Select Silver To Get Wholesale Prices

- Get your Vitamin B17 & Get 10% Off With Promo Code TIM

- How To Protect Yourself From 5G, EMF & RF Radiation

- Protect Your Income & Retirement Assets With Gold & Silver

- Grab This Bucket Of Heirloom Seeds & Get Free Shipping With Promo Code TIM

- Here’s A Way You Can Stockpile Food For The Future

- Stockpile Your Ammo & Save $15 On Your First Order

- Preparing Also Means Detoxifying – Here’s One Simple Way To Detoxify

The London firm was only too happy to write Feldstein’s considerable order, but with one caveat: a .600 NE would not be possible. Hollands had made its final .600 in 1975, announcing, certifying and assuring the customer who bought it that they would never turn out another one, which greatly enhanced that last .600’s collector value.

The H&H board of directors responded to Feldstein’s request and subsequent insistence to build him a .600 with an unequivocal and emphatic “No.” Furthermore, they took umbrage at his suggestion that they were wrong in their decision to stop making .600s, refusing to budge on the issue.

Not one to give in easily, Feldstein countered with his customary nonchalance, “Well, if you won’t build another .600, then make me a .700 H&H.”

The board thought the silly Yank had lost his mind, daring to order a Holland & Holland rifle in a ridiculously large and non-existent caliber. A mirthful outburst erupted at Feldstein’s expense—the board considered him impudent and marveled at the audacity of his proposing such a whimsical project.

When the laughter died down, the board calmly explained the many reasons why they would be hesitant to even consider his request for a .700. Feldstein’s interest, passion and fascination for guns over the course of his life had led him down a path culminating in that confrontation with Holland & Holland of London.

Interest In Africa

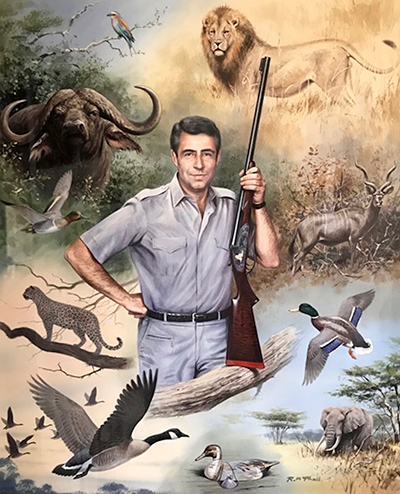

As a youngster, Feldstein discovered the writings of the early African explorers. Men like Sir Samuel Baker, William Cornwallis Harris and, of course, Henry Stanley and David Livingston fueled his interest in Africa and ultimately in big-bore rifles. Their exploits sparked a desire in Feldstein to follow in their footsteps through Darkest Africa. He dreamed of one day going there to face the same odds with the same rifles they had carried and upon which their lives had depended.

Feldstein sought out Africana over the years, eventually amassing a collection of around 400 written works of the early explorers. His notable assortment of fine books covered a period of African exploration spanning from the 1800s through the 1950s. His primary interest lay with the Victorian era of African exploration, and he was particularly drawn to the big-bore blackpowder cartridge rifles used by the men of that period.

“Many successful people have had mentors, and fortunately I met one of mine through my gun interest,” Feldstein recalls. “I had an affinity for large-bore blackpowder doubles from the mid-19th century, but finding ammunition was a problem. That was until I met Ray Meyer, a master at developing custom ammunition for the blackpowder guns, and who was still making bespoke 4- and 8-bore cartridges at the age of 78. It was through his methodical tutoring that I learned how to handle, shoot and respect those magnificent big-bore rifles from a bygone era.”

Once Feldstein became proficient with the 4- and 8-bore blackpowder guns, he began to indulge in the Nitro Express big-bores. It didn’t take him long to discover the difference between the shoving recoil of blackpowder guns and the sharper kick of the nitros. “Once I began shooting nitro calibers, the challenge to conquer recoil and withstand the subsequent punishment was paramount to accurate shooting. With lots of range practice, I was eventually able to accurately shoot large-bore calibers from .375 up. I learned that one must endure some discomfort and pain, but once you get the ‘hang’ of nitro, then it’s quite simply ‘mind over matter.’”

Guns On Safari

In the early 1970s, Feldstein realized a lifelong dream when he journeyed to East Africa with his family to experience his first taste of an African safari. Even though he shot only with a camera during that introductory adventure, it bolstered his determination to see more of Africa and to get to know the Dark Continent more intimately. He wanted to leave the “beaten path” for wilder parts of Africa where having a gun in hand was not only recommended but essential to survival.

Feldstein’s first hunting safari took place in 1975 in Botswana’s Okavango Delta with famed elephant hunter Wally Johnson. For the purposes of that safari, Feldstein carried a pair of Winchester Model 70 magazine rifles—the larger rifle chambered in .375 H&H Mag. He hunted Cape buffalo and plains game for the first time, and before that safari ended, Feldstein was planning the next one.

His next safari was a 21-day hunt in Tanzania, shortly after the country lifted a hunting ban in 1979. Conducting the safari was the late artist and former professional hunter (PH), David Schaefer. Traveling directly from Los Angeles to a remote bush strip in the Rungwa Hunting Concession located in central Tanzania, Feldstein felt great anticipation, for his would be the first safari in that historic hunting ground in several years. Feldstein’s major focus on that safari was elephant, for which he bought two licenses and brought a Rhoda double rifle in .450/400 NE.

“Schaefer was waiting at the airstrip when I arrived, and he took me back to camp in time for a late lunch, after which he suggested we take an afternoon drive for a look around the area,” Feldstein recalls. “I quickly unpacked my gear, changed into my hunting kit and assembled my Rhoda double rifle.

“Schaefer was waiting at the airstrip when I arrived, and he took me back to camp in time for a late lunch, after which he suggested we take an afternoon drive for a look around the area,” Feldstein recalls. “I quickly unpacked my gear, changed into my hunting kit and assembled my Rhoda double rifle.

“Leaving camp in the safari vehicle, we were barely out of sight of the mess tent when we heard an urgent tapping on the cab roof. Standing in the back of the vehicle, the trackers had spotted three bull elephants—a big tusker accompanied by two younger guardian [askaris] bulls. Schaefer jammed on the brakes and told me to bring my double. Fortunately, the afternoon breeze was favorable, and we were able to get within 15 yards of the trio.”

The large bull carried long, thick tusks, so without hesitation, Schaefer told Feldstein to shoot. Still jetlagged from the long plane ride, Feldstein stared at the bull elephant and, as a complete novice, failed to recognize the exceptional quality of the animal. He was unsure if he wanted to shoot an elephant within sight of camp on the first afternoon.

”Besides,” he thought to himself, “I’ve got 21 days to hunt and two licenses. What’s the hurry?”

Schaefer, knowing how fortuitous and fleeting this opportunity might be, became agitated at Feldstein’s reluctance to take the bull. He also knew that every second wasted increased the chances the elephant might get away from them. Schaefer quickly convinced Feldstein that he must take this bull, whose tusks he estimated would weigh around 80 lbs. apiece.

Fortunately, the three elephants did not move far from where they were first spotted. The trackers hung back while Schaefer and Feldstein crept up to a bush about 10 yards away from the elephants.

“I sat for a moment to give my pounding heart a chance to settle,” Feldstein remembered. “I then gathered the courage to stand and step in front of the bush, which immediately alerted the elephants. The big bull’s ears came forward, and he started toward us. At that instant, I raised the rifle and fired. Fortunately, the elephant dropped in his tracks from a frontal brain shot.” It was an explosive start to a safari that thrust Feldstein into the world of elephant hunting. The irony is that, for the next 20 days, the party hunted hard to find a second elephant but never saw another bull with tusks weighing more than 20 lbs.

After several successful elephant hunts, Feldstein began to seek out ever-more remote and primitive areas of Africa in which to employ his rifles, settling on Ethiopia, an area he considered to offer the best odds of producing a 100-lb. tusker (an elephant old enough and big enough to carry tusks weighing 100 lbs. or more per side). He made four foot safaris with PH Nassos Russos, solely for big tuskers, emulating the early ivory hunters, mostly using .577 and .600 NEs. Successful several times, he finally met the goal with an elephant whose tusks registered 100 and 104 lbs. But Feldstein was not interested in the acclaim afforded by the record books. He was in it purely for the challenge and his love of Africa—and big-bore rifles.

Feldstein’s affinity for British big-bore Nitro Express doubles contributed to an increasingly large rifle collection that became impressive by any standard. At one time, it included 15 blackpowder doubles in 12-, 10-, 8- and 4-bore, and 65 British Nitro Express doubles, six of them .600s, seven .577s, eight .500s, several .450s, as well as many medium- and small-bore rifles. He used most of the rifles he owned on safari and amassed more than 10,000 Nitro Express cartridges.

Cartridge & Rifle Design

Feldstein is quick to sum up his philosophy regarding the artistry and function of fine double rifles. “Most men who purchase English best-quality double rifles do not hunt with them because of their value. I believe to the contrary. In spite of their exceptional quality, these fine guns were designed and built to shoot. Men have devoted 1,400 to 1,500 hours of their time—is it not our responsibility as a tribute to their artistry to take the rifles into the field and use them for what they were built for?”

Holland & Holland eventually agreed to Feldstein’s proposal to build a .700, but the firm was extremely wary undertaking a scheme it considered to be somewhat impulsive and stipulated conditions that would have proved daunting to a man of lesser means and determination. The design and development of the cartridge and its provision in sufficient numbers to permit regulation of the barrels was to be Feldstein’s responsibility. Furthermore, the prototype barrels would have to be made at his expense. With no precedent for pressures and recoil energy, nobody could be sure it was even feasible. Holland & Holland’s reply to Feldstein came down to, “Design the cartridge, give us the specs, and we’ll talk again.”

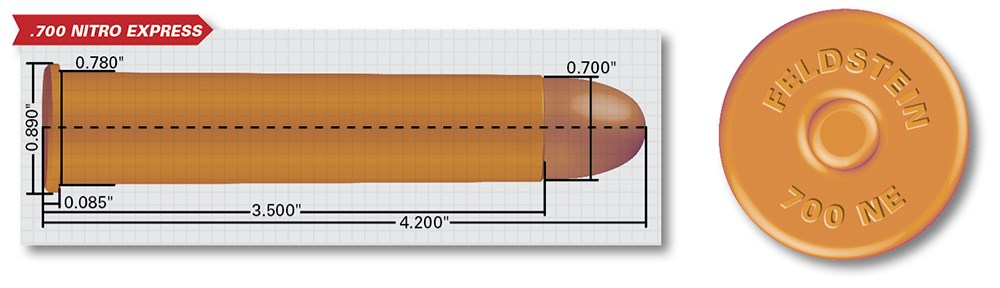

To begin the cartridge research, Feldstein elicited the services of Jim Bell, then president of Brass Extrusion Laboratories Ltd. (B.E.L.L.). Feldstein drew up plans for an original cartridge design, meaning that it was not based on altering the caliber or the configuration of an already existing cartridge. And while he was a fan of the .600 NE, he realized the blunt shape of its 900-grain bullet was not as effective a penetrator as the more streamlined .577 projectile. So Feldstein decided that the .700’s bullet should be of the .577 shape.

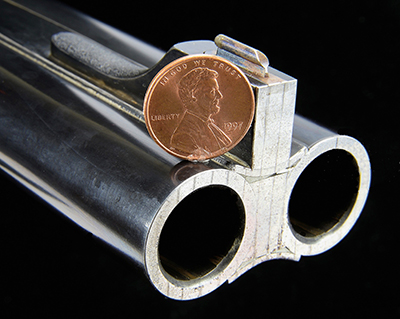

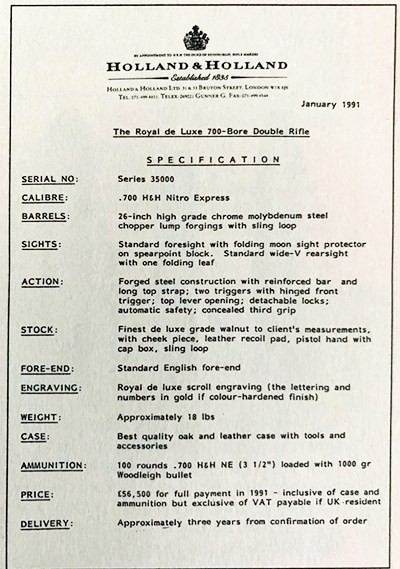

The .700’s case is based on an upscaled version of the .600 NE case, but at the same time, it’s a totally new case of larger diameter. It’s also longer by a full half-inch than the .600 case. At the end of their research, Feldstein and Bell had designed a cartridge using a 3½” case that accommodated a 1,000-grain, 0.700-cal. bullet. The loaded case and bullet measured a little over 4″ in total length. On paper, the ballistics showed the .700-cal. bullet would leave the muzzle at 2,000 f.p.s. and generate more than 9,000 ft.-lbs. of energy. There was no doubt that it would qualify as the most powerful sporting cartridge in the world.

Two critical questions still needed to be answered before the project could continue. First, could a conventional rifle weighing what an average man could handle withstand the tremendous recoil of such a cartridge? And, second, would the recoil be within acceptable limits of what an average man could absorb without injury? Even though individuals have a greatly varying amount of tolerance to recoil, a new and powerful .700 cartridge had to remain manageable for the majority of big-game hunters who might fire it.

There are two aspects of recoil to consider: the total recoil energy, which could be described as the overall force, and the “felt” recoil velocity. When the muzzle velocity of a bullet of a proposed cartridge has been calculated, it can then be used in an equation to calculate the recoil that the cartridge will produce when fired in rifles of different weights. A .30-’06 Sprg. with a 180-grain load produces nearly 20 ft.-lbs. of recoil. The .375 H&H Mag. generates twice the recoil of the .30-’06, and the .460 Weatherby, billed then as the world’s most powerful sporting rifle until the advent of the .700 NE, kicks with 80 pounds of recoil—twice as much as the .375 H&H Mag. The .700 NE produces 160 ft.-lbs. of recoil.

Bell calculated that the .700 H&H rifle would have to weigh 17 to 18 lbs., but to be certain, he’d have to lathe-turn brass cases, have bullets made, and have a test barrel weighing between 75 and 100 lbs. made by a specialist engineering company that would also make a standing breech of some kind. Another company would have to be engaged to make the rifling tools and cut the rifling. The preliminary cost was around $20,000. Feldstein thanked them, picked up the blueprints and flew back to London to present the plan to the H&H directors.

“They remained stone-faced,” Feldstein said. They stated that the project would have to “pass muster” with their factory manager, who spoke to Feldstein in a “pontifical manner” that was highly demeaning, frequently referring to “you Americans,” even though 50 percent of H&H’s annual production went to Americans, and Feldstein knew this. The manager apparently didn’t like Americans in general, and Feldstein in particular, and wanted the project scrapped. For the next year, the factory manager made Feldstein jump through many hoops. But eventually—when the board stepped in and reminded the manager that Mr. Feldstein was willing to place an order for four double rifles with all the bells and whistles—the factory manager backed off.

There were still a number of questions that had to be answered before the project could advance from the drawing board into the Holland & Holland workshops. What levels of pressure and force would the rifle have to withstand? What rate of twist was required for the rifling to stabilize such a bullet? And what degree of barrel convergence was needed to ensure tight grouping?

Furthermore, H&H was not willing to involve itself in the production of the cartridges. For that, Feldstein contacted Australian Geoff McDonald, owner of Woodleigh Gunsmithing, and put in an initial order of 5,000 bullets: 3,000 solids and 2,000 soft-nose. The solid bullets were made from cupro-nickel over a lead core, and the soft-nose bullets were a soft lead nose leading into a cupro-nickel cup. B.E.L.L., at the same time, began extruding cases for the bullets. The PMC/Eldorado Cartridge Co. undertook the loading of the cartridge—using 160 grains of Du Pont IMR 4064 powder and priming the huge case with Federal’s 215 Magnum Primer. Although H&H deemed Feldstein crazy for producing 5,000 .700 NE rounds, he viewed the cartridge like a proud father, claiming, “It’s the most impressive and beautiful cartridge in the world.” Critics of the project felt that producing 5,000 rounds was extremely excessive and wanted to know what possible need there was for that many cartridges of such a specialized and expensive chambering. Little did they know that, besides the potential owners of the .700 NE, cartridge collectors would snap up the rounds and, within 18 months, the entire lot of 5,000 was sold—mostly to collectors for $100 apiece.

Feldstein personally assisted in the regulation of the .700. In October 1989, three rifles were ready for regulating when he arrived in London with four days allocated to the chore. H&H provided two factory men to assist with regulating. During that time, Feldstein fired 55 rounds through the .700s, which, considering the cost of ammo at $100 per round, became quite a costly regulation.

“After firing a few rounds at 50 yards, I could see the irregularity of the ‘bullet print’ on the paper target,” Feldstein described. “I stepped away from the shooting bench while the two factory men heated the barrels with a large blowtorch to a temperature that allowed the steel to become malleable. Once the barrels were supple, one of the technicians took a large pair of tongs and gripped the wedge that was embedded in the rib in order to manipulate the barrels. The objective of adjustment is to bring the right/left barrels’ points of impact to within five inches of one another.”

Ultimate Field Test

By January 1990, a beautifully engraved double sidelock Holland & Holland Royal de Luxe prototype was completed. The range tests verified what the designers had calculated in the way of recoil: “about on par with a 10-lb. .500 Jeffery Rimless bolt-action with the character of a faster recoiling eight-bore.”

The field test for the new .700 was to be conducted on safari in the high-country game fields of Ethiopia during a 21-day elephant hunt. In March 1990, Feldstein, again accompanied by PH Nassos Russos, traveled to the Gambela region with the objective of hiking into the Guraferda Mountain Range.

“My final step was before me! Everything I’d endured, physical, mental and financial, could only be successfully concluded by taking an elephant with the .700,” Feldstein said. “I was prepared to hunt diligently on foot for 21 days in anticipation of shooting a bull elephant so I would prove conclusively that the .700 Holland & Holland Nitro Express performed as envisioned.” Feldstein intended to demonstrate that the .700 was not only a legitimate caliber and a feasible elephant gun, but also wanted to quiet all those who latently hoped that failure would be his fate. By mid-morning on the third day, they had found a wide, dishpan-size bull elephant track that looked promising.

“We tracked the bull through thick foliage for an hour and, judging by the freshness of spoor, he was not too far ahead,” Feldstein said. “We proceeded cautiously, stopping frequently to listen. Suddenly, the wind shifted, and instantly, we heard the elephant coming directly back at us. Even though I was in front, I could not see his body clearly through the thick foliage. When I saw his shape looming large through the leaves, I raised the .700 and pulled the front trigger, firing the right barrel. That stopped his charge, and I fired again, which turned the bull, who was quickly out of sight. We heard him crashing through the forest for about 60 yards before going down.”

“My shot signaled the end of the safari and the beginning of gun-making history,” Feldstein reflected. “After two days of rough travel, late that evening, I boarded a London-bound flight with the .700 in the baggage hold. The next morning, I returned my rifle to Holland & Holland so that they could complete work on the prototype. There, I related the story of my success. It was a proud moment describing how both cartridge and rifle performed as expected—the jacketed 1,000-grain bullet piercing the center of the elephant’s heart, at which time fantasy and dream became reality! It felt good to dream big and not let adversity dominate the conversation.”

Editor’s Note: The original price of $115,000 for a .700 H&H back in 1990 now looks like quite a deal. Today, expect to pay $400,000 and upwards for a basic .700 rifle, depending on order requirements. To date, Holland & Holland has built 17 double rifles in .700 NE, with No. 18 in current production.

Article by JOE COOGAN